[Download this issue brief as a PDF.]

This report was funded by a grant from the Anne and Henry Zarrow Foundation.

Finding affordable housing is one of the most difficult barriers faced by Oklahomans with a felony conviction in their past. Homelessness surveys and anecdotal reports from reentry programs indicate that inadequate access to housing is a substantial hardship for ex-prisoners. The inability to obtain housing hampers ex-prisoners’ efforts to reintegrate into society, rebuild their lives, and reunite with and provide for their families.1 These barriers may also result in formerly incarcerated people returning to environments that contributed to their initial trouble with the law.

Finding affordable housing is one of the most difficult barriers faced by Oklahomans with a felony conviction in their past. Homelessness surveys and anecdotal reports from reentry programs indicate that inadequate access to housing is a substantial hardship for ex-prisoners. The inability to obtain housing hampers ex-prisoners’ efforts to reintegrate into society, rebuild their lives, and reunite with and provide for their families.1 These barriers may also result in formerly incarcerated people returning to environments that contributed to their initial trouble with the law.

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development requires that applicants with prior criminal activity be excluded from subsidized housing only in the case of lifetime sex offenders and certain drug convictions. However, local housing authorities have substantial leeway to further restrict tenant eligibility. Local housing authorities have elected to exploit that leeway to varying degrees. The housing authorities’ applicant evaluation processes are vague at best, with little information available to the public. Similarly, a dearth of available data on rejected applicants makes it impossible to generate a definitive number of applicants with felony records accepted or rejected.

Providing affordable housing for the formerly incarcerated has clear benefits for society and the fiscal health of Oklahoma state and local government. Examples from major U.S. cities show that providing housing to individuals with felony records or substance abuse and mental health problems is more cost-efficient than the traditional array of homelessness support services.

In this report, we outline the regulations and restrictions that can exclude Oklahomans with criminal records from affordable housing. We then describe what data is available about those exclusions and their impact on individuals, families and communities. Finally, we recommend models to increase access to affordable housing and assess the potential for improvement in Oklahoma.

Current Policies

Affordable housing programs are administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD is a federally-administered, cabinet-level office with field offices throughout the states. The two primary HUD programs are public housing, where approved applicants live in residences owned by a local public housing authority (PHA), and Section 8, which grants vouchers to approved applicants for paying rent to participating private housing developments.

Under HUD policy, applicants must be denied assistance for life if (1) the applicant or a member of their household has previously been convicted for manufacturing methamphetamine in federally-assisted housing; or (2) the applicant or a member of their household is a lifetime registered sex offender.2 In order to be deemed a lifetime registered sex offender in Oklahoma, the individual in question must either be a “habitual or aggravated sex offender” or a “Level 3” offender.3 Applicants must be banned from HUD assistance for three years if the applicant or a member of the applicant’s household has previously been evicted from federally-assisted housing for drug-related activity. However, the ban may be lifted if the applicant or household member in question has successfully completed a public housing authority-approved treatment program, which may include drug court, or if the applicant household can prove that the individual who was cause for the eviction is no longer present, because “for example, the criminal household member has died or is imprisoned.”4

Additionally, applicants also must be denied HUD assistance if the PHA determines that any household member currently engages in illegal drug activity or the PHA has cause to believe that a household member’s current illegal drug use or pattern of illegal drug use may threaten the health, safety, or right to peaceful enjoyment of the premises by other residents.5 Federal statute requires the local PHA to establish standards to prohibit admission of households that fall under these categories.

Public Housing Authorities

Local PHAs administer HUD programs within cities and counties. The Tulsa Housing Authority (THA) and Oklahoma City Housing Authority (OCHA) administer HUD programs within the urban areas surveyed by this study, and the Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency (OHFA) covers parts of the state outside of the major cities. HUD field offices in Oklahoma City and Tulsa provide oversight and monitoring.

PHAs may not establish admissions standards more lenient than the code of federal regulations, but they may choose to tighten restrictions. For instance, a PHA could not choose to admit lifetime sex offenders into its Section 8 program. However, a PHA could choose to institute a permanent ban on non-lifetime sex offenders. PHAs are required to file tenant selection plans (sometimes called administrative plans), which detail more selective application policies, with HUD. There appears to be no requirement that these plans be readily accessible, although they may be released under the Freedom of Information Act.

Rejected applicants can request an informal hearing to appeal their rejection, but it is unclear to what extent the appeal process results in rejections being overturned. While one PHA suggested that the appeals process resulted in approval for a substantial number of applicants rejected due to criminal records, neither they nor any other PHA were able to provide data on the topic.

However, advocates say Oklahoma PHAs are in practice more stringent than the criteria in the tenant selection plan. In the case of the Tulsa Housing Authority, a “background screening and investigations policy” proved to be even more restrictive than the tenant plan indicated. The limited public information about PHA policies can make it very difficult for applicants to find out if they are eligible before applying. A number of service providers who deal with reentry indicated that most of their clients do not apply for housing assistance because they believe they are not eligible.

Tulsa Housing Authority

While the Tulsa Housing Authority maintains a detailed policy for applicant restrictions, most final decisions regarding applicants with criminal records are made on a case-by-case basis. The discretion exercised by Tulsa Housing Authority staff makes it difficult to determine beforehand which applicants will be admitted or denied.

The eligibility page of the Tulsa Housing Authority’s website links to the HUD code of federal regulations, which means additional restrictions exercised by the THA would be invisible to most applicants.

The Tulsa Housing Authority background screening and investigations policy states:6

…those individuals with a history of more than one arrest for crimes of violence, crimes that imposes [sic] financial cost, drug related activity, alcohol abuse, other criminal activity or crimes that threaten the health, safety, welfare or right to peaceful enjoyment of the premises may be deemed not suitable and denied admittance.

The document then lists examples of such crimes, including possession of controlled dangerous substances, public intoxication, and fraud. According to the policy, multiple arrests are considered enough “criminal activity” to exclude an applicant and their household, regardless of whether those arrests result in convictions.

The THA’s policy on non-lifetime sex offenders is also unclear. The THA’s Public Housing Tenant Selection Plan says that “THA will prohibit the admission to any federal housing program for any household that includes an individual subject to the State Sex Offender Registration Program,” implying that the THA ban extends to non-lifetime sex offenders.7 However, the THA background screening and investigations policy only mentions lifetime sex offenders. Most likely, decisions about non-lifetime offenders are made on a case-by-case basis.

The THA also notes in their background screening and investigations policy that a criminal background screening will be conducted “at least annually” on all adult household members. If this recertification process discovers a criminal history not previously revealed during the initial application process, “THA will pursue eviction or termination of assistance.”8 For example, an advocate recounted a call she received from a Tulsa woman for whom the recertification uncovered a years-old deferred sentence for paraphernalia possession, from when she was a teenager. THA terminated her assistance, and without a place to live, the woman dropped out of her college program one semester before graduation and moved herself and her children back to her hometown to live with her parents.

Oklahoma City Housing Authority

According to their website, the Oklahoma City Housing Authority Public Housing program bans households containing lifetime sex offenders and households containing members who have committed drug or violent crimes in the last five years.9 The Oklahoma City Housing Authority Section 8 program bans households containing lifetime sex offenders and households containing members who have committed drug or violent crimes in the last three years.10

The Oklahoma City Housing Authority’s Administrative Plan further allows the agency to deny applicants with household members who have, in the last three years, engaged in “criminal activity that may threaten the health, safety, or right to peaceful enjoyment of the premises by other residents or persons residing in the immediate vicinity.” This is determined by the “preponderance of evidence” and consideration of “all relevant circumstances…based on a family’s past history.”11 While the THA’s Security Plan further detailed precisely what criminal activity could result in an applicant’s exclusion, OCHA staff reported that they have no analogous document.

Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency

The Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency (OHFA) serves Oklahoma residents who do not live in cities or counties with their own public housing authority. In addition to the federal HUD guidelines regarding lifetime sex offenders and meth production in federally-assisted housing, the OHFA lists the following criteria for mandatory denial of assistance:

- Pattern of use of illegal drugs or abuse of alcohol, with no specific time period assigned, including “any record of convictions, arrests, or evictions of household members related to the use of illegal drugs or the abuse of alcohol.”

- The OHFA administrative plan then continues, “Testimony from neighbors, when combined with other factual evidence can be considered credible evidence.” As with the Tulsa Housing Authority, a pattern of arrests, regardless of whether they resulted in convictions, may be used to ban an applicant and their household, unless the applicant separates from the household, for an indefinite period of time.

- A ten-year ban if any household member has been charged, arrested or convicted of any crime involving meth. In this case, the agency mandates a 10-year ban following a single arrest, regardless of conviction.

- The OHFA’s policy regarding sex offenders is somewhat unclear. The OHFA bans non-lifetime sex-offenders for ten years following the date of the charge, arrest, or conviction, whichever is sooner. It is not clear whether being arrested but not convicted for a sex crime would qualify. It is possible that in such cases, the OHFA decides whether to approve or exclude applicants and their households on a case-by-case basis.12

Impact of these restrictions

Due to substantial gaps in data collection and aggregation, the full impact of these restrictions cannot be comprehensively measured. Of the three housing authorities examined in this study, only the Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency was able to provide data on the number of applications denied due to criminal activity/criminal background. However, the limited available data can be supplemented with other data and anecdotal information from reentry organizations to establish the general impact of barriers to ex-prisoners seeking affordable housing.

Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency

Since 2011, the Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency had received more than 25,000 applications. Of those applications, 1,903 were denied. A large majority of denials (1,460, or approximately 77 percent of all denials and 6 percent of total applications received) were due to violent crimes or drug crimes.

Oklahoma City Housing Authority

The Oklahoma City Housing Authority was unable to provide any information regarding the number of applications denied over any time period for any sort of criminal record/background, because the agency’s computer system does not aggregate data on denied applicants. Although denied applications must be held for three years following denial, staff claimed that there is no way to pull any data from those applications short of reviewing each one individually. OCHA Executive Director Mark Gillette reported that applicants who are not explicitly banned may be denied, but they may also demonstrate through an appeals process that they are stable and unlikely to be a threat. He did not provide any numbers showing how often the appeals process is pursued or how often it results in a denial being overturned.

Tulsa Housing Authority

The Tulsa Housing Authority chose not to provide any hard numbers. However, THA reported that from January 2012 through December 2015, 13 percent of applications received were denied because they “did not meet” the criminal background screening.

Other data

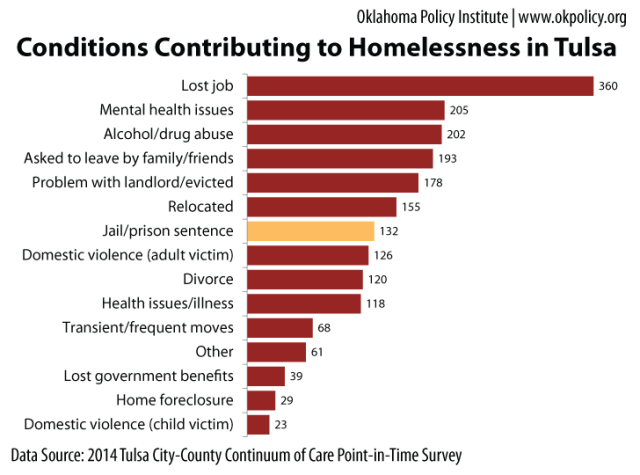

Point-in-time surveys conducted by homelessness organizations in Oklahoma City and Tulsa indicate that people with criminal records are overrepresented in the homeless population. The 2014 Tulsa point-in-time survey found that of 1,093 surveyed, 134 (12.3 percent) reported that jail/prison had contributed to their becoming homeless.13 The 2014 Oklahoma City point-in-time survey reported that out of 1,481 individuals surveyed, 265 (18.0 percent) reported spending time in jail in the prior six months, and 133 (9 percent) had been in prison within the last year.14

Data from organizations that work with people recently released from incarceration further indicates that a lack of affordable housing is a significant barrier to reintegration for their clients. Hope Community Services, an Oklahoma City-based non-profit that provides outpatient behavioral health services for a variety of populations, including those recently released from prison, reported that of 227 individuals served, only 29 (10 percent) had housing in place when they left prison. Of the remaining 198 individuals, 159 (80 percent) were denied housing due to a felony history.

Effects of restrictions

Organizations serving the formerly incarcerated uniformly said that a lack of affordable housing is a persistent barrier for both clients and the organizations that serve them. Furthermore, because they frequently work with ex-offenders over a period of time, these organizations are well-positioned to observe the effect of that housing shortage on the clients they serve.

Housing specifically for recently-released ex-offenders is in short supply. What housing is available is frequently provided by faith-based organizations, which can impose restrictions on residents’ schedules. Most of these organizations require residents to attend at least one religious service per week and other regular meetings, which one advocate noted can impair residents’ ability to locate and keep a job. While some reentry organizations have cultivated relationships with landlords or apartment management companies, these private housing providers frequently require higher deposits for ex-prisoner residents. This expense can divert reentry resources or impose another cost on ex-prisoners who are already likely to be facing numerous fines and limited opportunities for income.15 In short, to quote one organization, housing is “a huge issue.”

Lack of housing options can also increase the danger of recidivism. One advocate noted that the inability to locate housing following release means that clients often resort to living with family or friends that they were close to prior to their incarceration – who were often either directly or indirectly contributors to the behaviors or activities that led to incarceration in the first place. Furthermore, conditions attached to living with friends and family – providing unpaid childcare, for instance – can impede the former offenders’ ability to locate and hold down a job.

The situation is even more difficult for registered sex offenders, who are barred from most reentry programs, transitional living, private rentals, or any housing within 2,000 feet of a school or park. One advocate who works with former sex offenders pointed out that most buildings that are more than 2,000 feet from parks or schools are not zoned for residential habitation.16 A reentry specialist who requested anonymity suggested that a significant proportion of the homeless men in Tulsa and Oklahoma City are former sex offenders.

Barriers to housing are just one part of a web of challenges facing Oklahomans with felony convictions. The requirement that households may receive assistance only if they exclude household members whose activities led to their eviction adds to incarceration’s disruption of the family unit. Not being able to rejoin families not only breaks up family units, but may also increase cost of living as living with families is typically cheaper than living by oneself. Those with felony convictions are barred from many jobs, public safety net programs, and in some cases from obtaining a driver’s license.17 At the same time, we know that reintegration into communities decreases the likelihood of recidivism.18 While policies designed to protect the safety of other public housing residents are important, it becomes self-defeating when those policies go beyond what is sensible for protecting public safety and instead appear to serve as additional retribution after individuals have completed their sentences.

In 2011, HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan issued a letter to PHA executive directors urging – but not requiring – PHAs to be more lenient when evaluating applicants with prior convictions, in the name of reunifying families and lowering recidivism rates. Donovan wrote:19

People who have paid their debt to society deserve the opportunity to become productive citizens and caring parents, to set the past aside and embrace the future. Part of that support means helping ex-offenders gain access to one of the most fundamental building blocks of a stable life – a place to live.

However, according to HUD personnel we interviewed, Oklahoma PHAs have largely disregarded the letter. They did suggest that the Oklahoma City Housing Authority has made progress in allowing applicants a fair shot at making their case during the informal appeals process, for instance by demonstrating “evidence of rehabilitation and evidence of the applicant family’s participation in or willingness to participate in social services such as counseling programs.”20

Models for Reform

Several major U.S. cities have successfully pursued reforms to provide stable housing to residents with a felony conviction. Salt Lake City and County partnered to implement “housing first” policies designed to move both the chronically homeless (who may have criminal records) and recently-released prisoners into stable housing.21 The Housing Authority of New Orleans, following substantial criticism of a housing policy that kept large numbers of black men away from their families in a city with an incarceration rate well above the national average, has revised their criminal background policy to allow housing assistance to all but the most heinous offenders.22

Salt Lake County & City

In 2005, a partnership between a Salt Lake City shelter and the Housing Authority of the County of Salt Lake (HACSL) yielded a program credited with decreasing the state’s homelessness rate by 72 percent over nearly a decade.23 They implemented Housing First, “a program, or rather a philosophy” which works to get homeless residents into housing prior to focusing on other problems that they may face, such as addiction or mental illness.24 The project is funded by HUD via the Shelter Plus Care Program.

In the words of Sam Tsemberis, the psychologist who pioneered Housing First, conventional subsidized housing programs created “a long stairway that required sobriety and required stability in order to get into housing. So many people could never achieve that while on the street. You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around.”25 Indeed, the state found that giving people supportive housing cost the system about half as much as leaving them homeless.26 As the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness notes:27

We know that just one person experiencing chronic homelessness can cost communities between $30,000 to $50,000 per year in emergency room visits, hospitalizations, jails, prisons, psychiatric centers, detox programs, and other costly services. But solving the problem — connecting someone to permanent housing with the supportive services they need to achieve health and stability—only costs about $20,000 annually.

Similarly, the Housing Assistance Rental Program (HARP), in partnership with the City of Salt Lake and the Housing Authority of the County of Salt Lake, was designed to provide housing to homeless people within the criminal justice system by moving them into subsidized housing upon release from jail or mental health or substance abuse treatment facilities.28 According the Bureau of Justice Assistance:29

Without the rental assistance offered by HARP, these individuals are unlikely to be able to pay security deposits or meet rent obligations in the initial months after release. Failure to meet rent obligations has an impact not only on the tenant, but can have consequences for other people released from prison or jail. When tenants who have recently been released from corrections settings default on rent, landlords are less likely to accept future tenants with criminal records, further tightening the housing market for this group of individuals.

New Orleans

In 2013, the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) implemented new housing policy whereby HANO no longer automatically bars applicants from receiving housing assistance due to criminal records and/or backgrounds.30 When adopted, housing personnel said that while they expected it would have little impact on future applicants, it would allow a significant number of families already receiving assistance to reunify.31 As HANO noted:32

Their criminal history is likely a bar to admission to most affordable housing opportunities, making post-incarceration reunification of families a near impossible dream. We recognize that, whether explicit or implicit, its practices have served to perpetuate the problem … and accepts that it has a responsibility to give men and women with criminal histories the opportunity to rejoin their families and communities as productive members.

Furthermore, the Housing Authority also required that “anyone who wants to do business with HANO, whether as a contractor, consultant, or landlord…also adopt this policy.”33 This policy change is rather young; unlike the Salt Lake case described above, not enough time has passed to measure outcomes.

Conclusion

While Oklahoma’s barriers to housing are substantial, the examples of Salt Lake City and New Orleans, both in politically conservative states, show that a pro-housing policy for ex-prisoners is achievable. The limited available data on the prevalence or effect of denying subsidized housing to people with felony convictions in Oklahoma does make it difficult to demonstrate the scope of the problem. A first step for reforms to improve housing access may be requiring better data collection and transparency by housing authorities.

The City of Tulsa’s 2014 Analysis to the Impediments to Fair Housing Choice noted that NIMBYism (“Not In My Backyard”-ism, or neighborhood resistance to integrating low-income populations with the community) is already a substantial barrier to the creation of affordable housing. Lessening a prohibition against residents with felony convictions may add to that local resistance against new public or subsidized housing. However, the Mental Health Association Oklahoma’s demonstrated success with low-density supportive housing may provide a model for other types of affordable housing throughout the community.

Oklahoma’s criminal justice system has long persisted in punishing those convicted of a crime long after their time in prison or on probation has been served.34 However, recent developments give advocates reason to hope that the trend is reversing. Legislation passed in the 2015 legislative session begins to dismantle the web of restrictions that denies access to jobs for Oklahomans with criminal records. House Bill 2168 removes restrictions on obtaining job licenses for professions that do not substantially relate to their crime, and House Bill 2179 allows nonviolent offenders on probation to obtain a commercial driver’s license.

Housing policies that discriminate against ex-offenders still prevent reintegration into society, keep families apart, and perpetuate longstanding disparities in wealth and income. Reforming these policies and transitioning to a model that prioritizes housing for ex-offenders would fight recidivism, support the economy, and encourage stable families. For these reasons, improving access to affordable housing for ex-offenders should be an integral part of further criminal justice reform in Oklahoma.

Methodological Note

Local affordable housing policy is labyrinthine, and despite our best efforts, we cannot guarantee that we have captured the full universe of policies and regulations governing the provision of affordable housing assistance to people with felony convictions. All agencies discussed in this report were initially hesitant to engage on the subject. Although some became more forthcoming as the project went on, not all pertinent documents or data may have been provided.

Acknowledgements

This report was funded by a grant from the Anne and Henry Zarrow Foundation.

We also express our gratitude to the many individuals and organizations who contributed their contacts, time, and expertise to this report. They include the following:

- C. Lyn Larson of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Tulsa Field Office

- Terri Cole of the Tulsa Housing Authority

- Mark Gillette and Richard Marshall of the Oklahoma City Housing Authority

- Deborah Jenkins and Holley Mangham of the Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency

- Greg Shinn of the Mental Health Association Oklahoma

- Bob Mann of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections

- Wanda DeBruler, Edmond

- Dan Straughn of The Homeless Alliance, Oklahoma City

- Amy Santee of the George Kaiser Family Foundation

- Robert Scott of Hope Community Services, Incorporated, Oklahoma City

- James Womack of Hand Up Ministries, Oklahoma City

- Dolores Verbonitz of Tulsa Re-Entry One Stop

- Cathy Hodges of Resonance Center for Women, Tulsa

- Kelly Doyle of The Center for Employment Opportunities, Tulsa

- Missy Brumley of The Education and Employment Ministry, Oklahoma City

- Barbara Foster of Wings of Freedom, Tulsa

References

- Wright, Kevin A., and Gabriel T. Cesar. “Toward a More Complete Model of Offender Reintegration: Linking the Individual-, Community-, and System-Level Components of Recidivism.” Victims & Offenders 8.4 (2013): 373-98. Web.

- “Housing and Urban Development” 24 CFR 960.204.

- For more information on habitual or aggravated sex offenders, “Sex Offender Registration Level Assignment” http://www.ok.gov/doc/documents/020307e.pdf and 21 OS 1114. For more information on sex offender level assignments, see “Prisons and Reformatories” 57 OS 584N1 and 57 OS 584N2.

- “Denial of admission and termination of assistance for criminals and alcohol abusers.” 24 CFR 982.553B

- Ibid.

- Tulsa Housing Authority. “Background Screening and Investigations.”

- Tulsa Housing Authority. “Public Housing Tenant Selection Plan.”

- Tulsa Housing Authority. “Background Screening and Investigations.”

- Oklahoma City Housing Authority. “Public Housing Eligibility and Income Limits.” http://www.ochanet.org/WEBTEST/section8%20info/Section%208.htm.

- Oklahoma City Housing Authority. “Section 8 Eligibility and Income Limits.” http://www.ochanet.org/WEBTEST/section8%20info/Section%208.htm.

- Oklahoma City Housing Authority. “Administrative Plan.”

- Oklahoma Housing Finance Agency. “Administrative Plan.”

- Community Service Council. 2014. “2014 Tulsa City-County Continuum of Care Point-in-Time Survey.” http://www.csctulsa.org/files/file/2014%20Point%20in%20Time%20Survey%20Results%20-%20Tulsa%20Format.pdf.

- Community Development Division, Oklahoma City Planning Department. 2015. “2014 Point-in-Time: A Snapshot of Homelessness in Oklahoma City.” http://www.homelessalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2014-OKC-Point-In-Time-Report-Final.pdf#page=13. Specific information on survey questions was provided by the Homeless Alliance.

- Oklahoma Policy Institute. January 2015. “Every sentence is a life sentence: 3 barriers to life after prison.” https://okpolicy.org/every-sentence-life-sentence-3-barriers-life-prison.

- Oklahoma Department of Corrections. Oklahoma Sex Offender Registry. http://sors.doc.state.ok.us/svor/f?p=105:1.

- Oklahoma Policy Institute. January 2015. “Every sentence is a life sentence: 3 barriers to life after prison.” https://okpolicy.org/every-sentence-life-sentence-3-barriers-life-prison.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2012. “Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders.” http://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/crimeprevention/Introductory_Handbook_on_the_Prevention_of_Recidivism_and_the_Social_Reintegration_of_Offenders.pdf#page=18.

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. June 2011. “Reentry letter from Shaun Donovan to PHAs.” http://usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Rentry_letter_from_Donovan_to_PHAs_6-17-11.pdf.

- Ibid.

- The Washington Post. March 2015. “’Housing first’ approach works for homeless, study says.” http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2015/03/04/housing-first-approach-works-for-homeless-study-says/.

- Formerly Incarcerated and Convicted People’s Movement. 2013. “Communities, Evictions & Criminal Convictions: Public Housing and Disparate Impact: A Model Policy.”

- Housing Authority of the County of Salt Lake. “Supportive Housing Programs.” http://www.hacsl.org/rental-assistance/homeless-programs.

- Mother Jones. March/April 2015. “Room for Improvement.” http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/02/housing-first-solution-to-homelessness-utah

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. June 2014. “USICH Blog: 101,628 People Are Now in Safe and Stable Homes!” http://usich.gov/blog/101628-people-are-now-in-safe-and-stable-homes.

- Salt Lake County. “Housing Assistance Rental Program (HARP).” http://www.slco.org/crd/housing/rentalHARP.html. And The Council of State Governments Justice Center. 2010. “Re-entry Housing Options: The Policymakers’ Guide.” http://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Reentry_Housing_Options-1.pdf#page=22.

- Ibid.

- The Housing Authority of New Orleans. September 2014. “Admission and Continued Occupancy Policy (ACOP) Amended and Revised.” http://www.hano.org/home/agency_plans/Amended%20Revised%20ACOP%209-30-14%20FINAL.pdf.

- Louisiana Weekly. May 2013. “HANO adopts new criminal background policy.” http://www.louisianaweekly.com/hano-adopts-new-criminal-background-policy/.

- The Times-Picayune. March 2013. “Public housing residents optimistic about HANO’s new criminal background check policy.” http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2013/03/public_housing_residents_optim.html.

- The Times-Picayune. January 2013. “HANO to change resident policy on criminal background checks.” http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2013/01/hano_to_change_resident_policy.html.

- Oklahoma Policy Institute. January 2015. “Every sentence is a life sentence: 3 barriers to life after prison.” https://okpolicy.org/every-sentence-life-sentence-3-barriers-life-prison.

OKPOLICY.ORG

OKPOLICY.ORG