Note: References to the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in this article will focus on the federal laws, unless otherwise specifically referencing Oklahoma’s state laws related to the Indian Child Welfare Act.

—

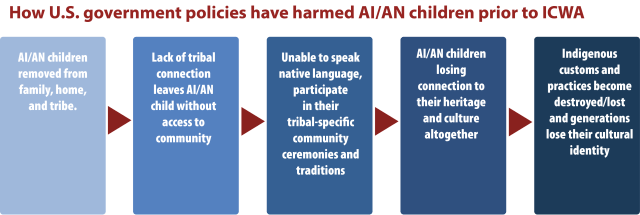

As a state with a high population of American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) children and overall low ranking in general child well-being, it is crucial that Oklahomans understand what the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) means for child well-being in the state. ICWA is a federal law that passed in 1978 as a response to the high number of AI/AN children being removed from their homes by both private and public agencies and placed in non-AI/AN homes, institutions, and adoptive homes. These forced removals effectively continued harmful historical practices of assimilation, cultural erasure, and ethnic cleansing for AI/AN peoples in America. AI/AN children are the future of tribes — without them, there is no tribe. In order to understand ICWA’s importance today, one must understand Indian child welfare history and how this federal legislation guards against continued cultural genocide by protecting AI/AN children’s connection to their culture and preserving tribal sovereignty.

The legal case of Haaland v. Brackeen, currently pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, focuses on federal ICWA laws designed to help protect both the well-being and cultural identity for AI/AN children. If the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the federal ICWA, this would create devastating harm to tribal sovereignty and endanger AI/AN children in child welfare systems. Should the federal law be overturned, tribal and state leaders in Oklahoma could collaborate using the state’s ICWA laws (Okla. Stat. § 40.1-9) to help ensure the well-being of AI/AN children in the state.

The Indian Child Welfare Act exists to protect AI/AN youth in the child welfare system

Although AI/AN communities have historically been displaced, relocated, removed, and taken from their homes, they are still rooted in deep traditions. Based on AI/AN political and cultural identity and the relationship to the federal government, the ICWA established a distinct type of protection for AI/AN children so that active efforts would be made to maintain or reunite AI/AN children with their families. Before ICWA was passed, up to 1 in 3 of all AI/AN children were removed from their homes and communities, and the children were placed in non-AI/AN foster care placements, adoptive care, or institutions. Previous legislation — such as the Indian Civilization Act Fund and Peace Policy of 1869 that led to AI/AN boarding schools (1819-1969) and the Indian Adoption Project (1958-1967) — weakened and destroyed tribal family structures. The 1978 adoption of ICWA aimed to reverse these harmful practices and meant that tribes now had jurisdiction over child welfare cases involving their tribal citizens. The ICWA guidelines focus on preserving AI/AN identity, culture, family, and tribal connectedness.

Unfortunately, the AI/AN distinction in ICWA has been sorely misunderstood as a sole “race” classification; ICWA is intended to be an equitable protection-based policy to correct U.S. ethnic cleansing practices by granting tribes the right to decide what’s best for their children in care. To put it in perspective: For many of people, culture is an important resilience factor. Without ICWA’s protections, AI/AN children are denied access to their tribal culture, language, traditional dances, and ceremonies to name just a few. Whether it be the tribe or the state, someone needs to show up and protect the well-being of AI/AN children. The best way to achieve preservation of AI/AN children’s cultural identity is for active efforts, as defined by ICWA, to be made so that the children can remain and/or be reunited with their respective family, extended family, or tribe.

The Indian Child Welfare Act preserves AI/AN culture, identity, and community across the state

ICWA requires “active efforts” to maintain AI/AN youths’ connection to their family and community. This means that state child welfare systems must make affirmative, active, thorough, and timely efforts in caring for an AI/AN child to maintain or reunite them with their family. These efforts should be conducted in partnership with the AI/AN child’s parents, extended family members, Indian custodians, and tribe. Active efforts are more intense than the legal term “reasonable efforts” and applies to providing remedial and rehabilitative services to the family before removing an AI/AN child from their parent or Indian custodian and/or an intensive effort to reunify an AI/AN child with their parent or Indian custodian. Because widespread removals of AI/AN children from their tribes and placements with non-AI/AN families is a catalyst for the creation of ICWA, it makes sense that the law’s implementation hinges on actively ensuring AI/AN identity is prioritized.

While ICWA is intended for the well-being of AI/AN children, the values embedded in ICWA have been recognized as the “gold standard” in child welfare. For example, ICWA focuses on an AI/AN child’s rights to remain connected with their families and tribes. This is an important principle for general child welfare practice, as connectedness to family and community are important for child well-being. The “active efforts” requirement is also a higher standard of care than “reasonable efforts,” which also elevates child welfare practice. ICWA also values inclusive and diverse cultural practices by requiring child welfare agencies to view child welfare matters from a different cultural perspective. Finally, by seeking to deliberately reverse centuries of cultural erasure, it addresses harm inflicted on AI/AN families, culture, and traditions.

When implemented, the Indian Child Welfare Act strengthens Oklahoma families, communities, and tribes

A government-to-government partnership between the state and tribes creates a stronger tribal-state court collaborative, allowing proactive coordination to protect AI/AN children. Complying with ICWA and meeting its legal mandates helps ensure AI/AN children receive services afforded to them under the law. Furthermore, kinship (familial relationship) care has profound benefits to children’s mental health, economic, and educational well-being. Oklahoma has intergovernmental agreements known as Title IV-E Agreements and state ICWA legislation to protect and support AI/AN children and families.

However, ICWA only works when actively implemented. AI/AN children are still disproportionately represented in child welfare systems nationally. One national study found that due in large part to systematic bias, where abuse has been reported, AI/AN children are two times more likely to be investigated, two times more likely to have allegations of abuse substantiated, and four times more likely to be placed in foster care than white children. The overrepresentation of AI/AN children in the child welfare system is demonstrated through reports of abuse and neglect at rates higher than their overall population proportions. These rates grow higher at each major decision point in child welfare, such as ordering an investigation, substantiating those allegations, and whether to remove a child from their home and place them in foster care.

In November 2015, a review of ICWA in Oklahoma found that “outcomes for AI/AN children in out-of-home care in Oklahoma can be impacted significantly by the ICWA practices of child welfare services and state courts and the involvement of tribes in ICWA cases.” The snapshot indicates there is still a need for comprehensive ICWA compliance, coordination, and evaluation to better serve our children. In order to adequately implement ICWA, tribes should always have an open invitation to coordinate with caseworkers, policy analysts, and other state agency leaders on further developing and determining how to apply ICWA in their practice. Tribal case workers may not always have the resources to provide needed services, but they can advise on specific cultural differences and difficulties AI/AN children and families face. This would alleviate confusion and solidify an equitable process in implementing ICWA in state courts and child welfare agencies.

Child custody professionals also need to be transparent about current practices, gather and provide data, and be receptive to contexts provided by tribes to better adopt and apply ICWA. ICWA protects AI/AN children, but it also presents an opportunity for better tribal-state policy development as there is still a need for building capacity and improving child welfare practice among states and tribes. A 2015 national study found that only 17 percent of AI/AN children in out-of-home care live with an AI/AN caregiver, demonstrating that ICWA has yet to be fully implemented.

Oklahoma ICWA can help improve the state’s overall child well-being if fully implemented

When the state and tribes do not coordinate on child welfare, Oklahoma children and families are harmed, as well as their community and tribes. This has consequences for Oklahoma’s overall child well-being. Oklahoma’s existing state ICWA statute could protect AI/AN children and families if the federal ICWA is overturned. Adhering to the state ICWA statute could also help strengthen AI/AN child well-being if state officials work with the tribes on continuous implementation should the federal law be overturned.

When the state and tribes do not coordinate on child welfare, Oklahoma children and families are harmed, as well as their community and tribes. This has consequences for Oklahoma’s overall child well-being. Oklahoma’s existing state ICWA statute could protect AI/AN children and families if the federal ICWA is overturned. Adhering to the state ICWA statute could also help strengthen AI/AN child well-being if state officials work with the tribes on continuous implementation should the federal law be overturned.

ICWA has increased the national share of AI/AN children in care who are placed in kinship care. In 2016, the most recent year for which data are available, 35 percent of AI/AN children were in kinship care, compared to 31 percent of Black children and 32 percent of white children. Now, however, the Supreme Court is poised to rule on Haaland v. Brackeen, on whether tribes can continue to exercise their tribal sovereignty in protecting AI/AN children — the very heart of ICWA. Tribal governments, like state governments, care deeply about the safety and well-being of their children and families. ICWA is a vital area where tribal and state governments can work together to better define child welfare opportunities to strengthen ICWA implementation. In doing so, it would also advance our overall child well-being as well.

OKPOLICY.ORG

OKPOLICY.ORG