The federal ‘Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations‘ (FDPIR) program provides food assistance to low-income Native American households living in Indian Country. Many households participate in FDPIR as an alternative to SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), formerly the food stamp program, because they do not have easy access to SNAP offices or grocery stores. The agency that administers the tribal food program, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), recently proposed new regulations that would eliminate the program’s ‘asset test’, currently set at $2,000-$3,250.

The federal ‘Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations‘ (FDPIR) program provides food assistance to low-income Native American households living in Indian Country. Many households participate in FDPIR as an alternative to SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), formerly the food stamp program, because they do not have easy access to SNAP offices or grocery stores. The agency that administers the tribal food program, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), recently proposed new regulations that would eliminate the program’s ‘asset test’, currently set at $2,000-$3,250.

‘Asset-tests’ are sometimes used alongside income to determine a household’s eligibility for public assistance. For instance, a low-income household might otherwise have qualified for the tribal food program because their earnings were below the poverty-level, but because they had over $2,000 in a savings account, they became ineligible for assistance. CFED explains the original rationale behind asset-limits, and their irrelevance today:

If individuals or families have assets exceeding the state’s limit, they must “spend down” longer-term savings in order to receive what is often short-term public assistance. These asset limits, which were originally created to ensure that public resources did not go to “asset-rich” individuals, are a relic of entitlement policies that in some cases no longer exist. Cash welfare programs, for example, now focus on quickly moving individuals and families to self-sufficiency, rather than allowing them to receive benefits indefinitely.

Programs designed to help the poor should reward those who save. Asset tests do the exact opposite; they discourage families from saving because recipients risk losing benefits if they begin to accumulate assets – including donations they might receive from relatives, their faith group, or some other charity. People cannot escape poverty unless they begin to build-up savings to prepare for long-term financial security and protect themselves against unforeseen events – like medical bills, car repairs, or temporary unemployment. Nearly half of Oklahoma households (48.2 percent) and a majority of the state’s minority households (65.5 percent) do not have enough money in the bank to subsist at the poverty level for three months if they lost their income. Low-income households are particularly vulnerable to financial emergencies, as many have trouble making ends meet and are ill-positioned to save.

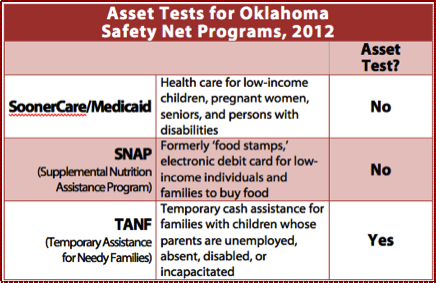

Of the three main state programs that assist poor families in meeting basic needs, only the TANF program uses an asset-test to determine eligibility. Families who are income-eligible for TANF must also have less than $1,000 in ‘assets’ (cash, savings, a vehicle) to qualify for benefits. Up to $5,000 of a vehicle’s equity is exempt from this requirement. The state’s Medicaid and food assistance program do not exclude families from eligibility because they’ve accumulated certain basic assets, like a car or a savings account:

Asset limits expose a fundamental tension inherent in providing basic benefits to impoverished families. Without higher wages, or lower monthly costs, the prospects for low-income people to transition out of poverty are bleak. Programs that are designed to provide a subsistence level of support should be sensitive to the precarious financial position of their recipients, and work to support those families in every way possible. By threatening to withdraw the benefits that they may need desperately in the short-term, asset limits prevent program participants from ever escaping poverty by sanctioning those who are fortunate enough to be moving towards long-term financial stability.

OKPOLICY.ORG

OKPOLICY.ORG