Dr. Gobar will be visiting Oklahoma to present the results of her research in full. She will be speaking Wednesday night, March 15th at the Oklahoma City Memorial Museum and Thursday night March 16th at the Mayo Hotel in Tulsa. Click here to RSVP and view more information about these events and here for a presentation on the racial wealth gap.

The boom in subprime mortgage lending in the early 2000s is widely recognized as the underlying cause of the country’s recent financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession. Subprime mortgages are loans offered at interest above the prime rate. When millions of homeowners began to default on their high-interest subprime mortgages in 2007, the bottom fell out of the housing market. This set off a chain reaction that threatened the nation’s largest financial institutions, who had sunk trillions into unsustainable mortgages on overvalued properties. Much of the blame falls on the financial institutions themselves, whose predatory practices and reckless behavior has since been scrutinized and rejected.

This post examines the subprime lending boom in Oklahoma, where the housing market continues to outshine harder-hit states. In many other states (particularly Arizona, Nevada, Florida, and California), widespread foreclosures and plummeting home values have hampered economic recovery. How bad was the housing crisis in Oklahoma? The following data are from a research paper by Dr. Angela Gobar sponsored by Howard University’s Center on Race and Wealth. Dr. Gobar’s paper, which you can view here, analyzed mortgage loans originated in Tulsa and Oklahoma City during and after the subprime lending boom. The two ‘metropolitan statistical areas’ examined in the paper contain 60 percent of the state’s population and are representative of the housing market overall.

This post examines the subprime lending boom in Oklahoma, where the housing market continues to outshine harder-hit states. In many other states (particularly Arizona, Nevada, Florida, and California), widespread foreclosures and plummeting home values have hampered economic recovery. How bad was the housing crisis in Oklahoma? The following data are from a research paper by Dr. Angela Gobar sponsored by Howard University’s Center on Race and Wealth. Dr. Gobar’s paper, which you can view here, analyzed mortgage loans originated in Tulsa and Oklahoma City during and after the subprime lending boom. The two ‘metropolitan statistical areas’ examined in the paper contain 60 percent of the state’s population and are representative of the housing market overall.

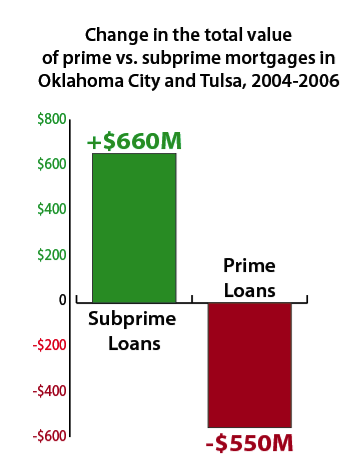

Oklahoma City and Tulsa experienced their largest volume of subprime lending as well as their widest interest rate spread during 2006. For both Tulsa and Oklahoma City, the average rate spread between a prime and a subprime mortgage loan peaked at 5 percentage points in 2006. So for instance, if the average prime mortgage was offered at 5 percent, then the average subprime mortgage loan was financed at 10 percent. The total volume of subprime lending soared between 2004 and 2006 and likely displaced much of the market’s prime lending activity, which plummeted during that same period.

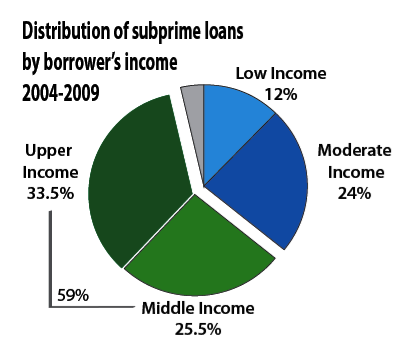

The majority of subprime loans in Oklahoma City and Tulsa went to middle and upper income borrowers. This goes a long way towards dispelling a popular myth that the housing crisis was caused by government programs that encouraged and supported homeownership among low-income Americans. Instead, these data support an alternative explanation: many borrowers who may have qualified for prime rate financing were steered into subprime mortgages by agents looking for higher commissions and working for unscrupulous lenders. The Justice Department successfully prosecuted mortgage giant Countrywide Financial on exactly those grounds, further charging that the corporation targeted minority communities. Other mortgage banks have also been accused of using discriminatory tactics to issue subprime loans:

Wells Fargo stands accused of using those same practices, but deploying them against black borrowers in majority-black neighborhoods, an act commonly known as “reverse redlining.” The city alleges that the bank targeted black borrowers, knowing they’d ultimately default on their loans, but did not fear shouldering the cost because Wells sold those loans to investors.

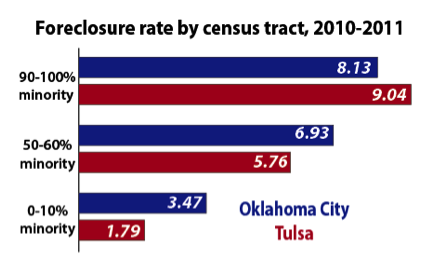

The data from Oklahoma City and Tulsa are consistent with allegations of ‘reverse redlining’. The percentage of subprime loans issued by race were consistent with each MSA’s demographics, but the study found that subprime lending was more concentrated in minority communities. So while overall the foreclosure rate in Oklahoma was comparatively mild during and after the housing crisis, when examined by census tract, foreclosures rates were much higher in communities where minorities were a majority of the population:

Much like the rest of the country, the share of subprime home loans in Oklahoma as a percentage of all home loans began to plummet in 2007. Subprime loans went from comprising about a third of the market for mortgage loans in Oklahoma in 2006 to less than a tenth of the market in 2009. Foreclosure rates in the aftermath of the subprime lending boom were so high in many states that they wreaked havoc on local economies. Oklahoma, however, was widely celebrated for coming out of the recession and housing crisis relatively unscathed. This study reminds us that this narrative does not apply across the board. Not even Oklahoma was immune from the subprime lending boom and the foreclosure crisis is being keenly felt in the minority communities of the state’s two largest urban centers.

Much like the rest of the country, the share of subprime home loans in Oklahoma as a percentage of all home loans began to plummet in 2007. Subprime loans went from comprising about a third of the market for mortgage loans in Oklahoma in 2006 to less than a tenth of the market in 2009. Foreclosure rates in the aftermath of the subprime lending boom were so high in many states that they wreaked havoc on local economies. Oklahoma, however, was widely celebrated for coming out of the recession and housing crisis relatively unscathed. This study reminds us that this narrative does not apply across the board. Not even Oklahoma was immune from the subprime lending boom and the foreclosure crisis is being keenly felt in the minority communities of the state’s two largest urban centers.

OKPOLICY.ORG

OKPOLICY.ORG

One thought on “Oklahoma's Housing Crisis: How bad was it?”